As the sun fell below the trees along the banks of the Saline River in Southern Arkansas, I finished my grilled bream caught just hours earlier. Soon, I grabbed the canteen from my backpack and started hauling small portions of river water back to the sandbar where my tent was pitched and began the process of putting out my campfire.

With that done, I decided to pack it in for the night. Once inside the tent and laid down on top of my sleeping bag, it became abundantly clear that I would get absolutely no sleep the entire night. No, there was no annoying noise from the woods keeping me awake, and there were no bugs trapped inside the tent pestering my face. No, no. Unfortunately neither of those were the problem. The problem was that it was the middle of June, and I was in Southern Arkansas inside a tent with no air conditioning. It wasn’t just hot. It was horribly humid, and my body was sweating like crazy. I felt as if I had just fully immersed myself in the river just yards away, but I hadn’t. It was just an Arkansas summer. While I wouldn’t get a good night’s sleep, this was exactly why I came on this expedition. I wanted to experience what life might have been like for the army of Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto who travelled through Arkansas between 1541 and 1542.My experience lasted only two nights, and to say my journey was less difficult than the Spaniards would probably be the understatement of the the last millennium. However, in my two-night stay along the banks of the Saline River in the middle of June, I did come to the realization that to feel any comfort at all in this hot and humid June Arkansas I would need to learn to live without much clothing. With that thought in mind, I find it interesting that most depictions of de Soto and his army show them in full armor.

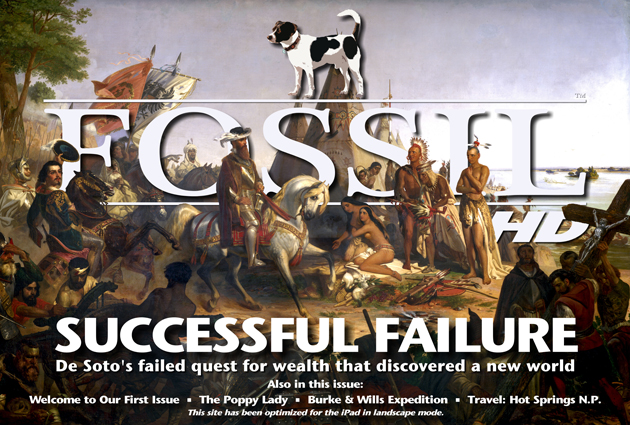

In fact, what is probably the most famous painting of de Soto, Discovery of the Mississippi(on the cover), shows almost all of the men of the expedition decked out in shiny metal armor and dressed in long sleeve formal battle attire. Keep in mind that by the time the Spanish expedition discovered the Mississippi, they had already been on the continent for quite some time and most likely were living more like natives than Spanish soldiers. However, that wouldn’t have made for a great painting. It also would not have made the natives look as if they were the most uncivilized beings ever seen on the planet. In fact, had the painting shown de Soto dressed in deerskin and clad in mud, then visitors to the United States Capitol, where the painting is kept, would probably think de Soto had been a complete failure in that he and his rag tag band of soldiers had resorted to living like what Europeans at the time perceived as savages. Instead, he took a more romanticized option and placed de Soto in striking formal attire and metal armor. Unfortunately, the painting by William H. Powell wasn’t done to depict history accurately and that’s, too, bad. Had Powell chosen the more historically accurate version, he would have actually been telling the story of a major success. The fact that the Spanish explorers had resorted to basically living like the natives meant that the soldiers were able to adapt to the way of life that would best help them survive and complete their mission. It would have shown that de Soto was a true veteran of exploration that was smart enough to realize that armor and wool were not going to cut it in 102 degree sweltering heat and high humidity.

That is just one of the many semi-false stories presented about the de Soto expedition all the time. In schools all across the United States and in countless books on the subject, de Soto and his quest throughout the modern Southeastern United States is told as if the man had completely failed. Most people are taught that this trip was a disaster of epic proportions. Again, this is semi-false. Just as in the famous Apollo 13 NASA mission, the de Soto expedition could be called a “successful failure.”

What we know:

Hernando de Soto was born into what we would call today a middle class family. Just like many other young Spaniards of the 1500’s de Soto joined the military in hopes of crawling the social ladder to a higher rung. His first trip to the newly discovered western hemisphere occurred in 1514. He travelled with a contingent of soldiers with the first Governor of Panama, Pedrarias Dávila. De Soto gained fame in a very short period of time. Known for his superb leadership skills and unbelievable charisma, de Soto became a Spanish icon, almost like General William T. Sherman during the American Civil War, for his trademark cunningness and combative expertise during the Mesoamerican Conquest.

After taking part in both the conquest of the Aztecs in Central America and later Peru, de Soto found himself a rich man. Fame and riches were soon followed by marriage and a close relationship to King Charles of Spain. Those royal ties rewarded de Soto with the Governorship of Cuba, which at the time could have been seen as the Capitol of all the eastern portion of Spanish North America.

Not content to settle for riches alone, de Soto yearned for the opportunity to take on his own expedition. That opportunity came along as a package deal with being the Governor of Cuba. He was soon given the task of exploring la Florida and colonizing it within the next decade.

For de Soto, this expedition was the adventure of a lifetime. While he had been a member of expeditions in the past in Mesoamerica and South America, the younger Spanish warrior had never before lead an entire army. This was his chance to cement his place in the chronicles of history.

King Charles set specific goals for this expedition. The army was to explore the land of la Florida and search for a water route to the Pacific. The Spanish crown also instructed de Soto to establish deeper relations and learn more about the native inhabitants of the area.

The army of Hernando de Soto would be embarking on a journey much like that of Lewis and Clark. They would be exploring a land virtually unknown to men of Europe. This was a land that in all honesty, the Spanish had little to no clue about the actual size. While they fully intended to search for a waterway to the Pacific and establish better connections with the natives, the men of the expedition and de Soto himself had other goals in mind. Like every other Spanish exploration at the time, one major dream was finding the riches that so often came with conquering native civilizations that had stood for thousands of years. Gold was a top priority. There is even some indication that de Soto was personally searching for a place rumored to exist deep inside the interior of North America along the banks of a large river that supposedly was a cliff made entirely of one humongous emerald!

These were the hopes and dreams of young men traveling to what at the time could have been considered a completely different world! No doubt these goals were lofty, but they were the norm for the Spanish.

Opposing Viewpoints

Ever since the death of Hernando de Soto and the imperfect completion of his army’s expedition, many scholars have formed the opinion that this Spanish expedition was more of a tyrannical attack on natives and ultimately a failure. While I don’t disagree that in some ways this expedition could be viewed as a failure,we may be selling de Soto a bit short if we do not look for the successes. After studying the details of the de Soto venture into the Southeastern portion of North America, and talking with several scholars of the subject I have come to the conclusion that the de Soto expedition should be deemed a “Successful Failure.”

What makes this a “Successful Failure?”

In 1539 Hernando de Soto’s army, which consisted of 620 men, 220 horses, a large number of hogs, and a pack of war hounds, landed near modern day Shaw’s Point in Bradenton, Florida. The army moved North along the western coast of Florida. Along the way they were met by many native groups, some friendly, some not friendly. Between 1539 and 1541 the army wound it’s way through some of the thickest forests and toughest terrain in the Southeast. They crossed through Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi. All the while, the Spanish left a wake of disease, destruction, and death. Little evidence still survives today other than several beads that lend a clue as to the route of the de Soto Expedition. The World does however have written accounts by several men with the army describing the events that took place along the way, further providing clues to the expeditions route. The accounts are the direct observations by the King’s Agent Fernandez de Biedma, de Soto’s personal secretary Rodrigo Rangel, and a Portuguese officer who we only know as a gentleman of Elvas. Even with these accounts, it is still very difficult to pinpoint the route of the Spanish. The biggest problem historians and archaeologist face today is that many rivers have changed course and landmarks have been altered or eroded over the hundreds of years since the expedition.

Failures:

Geographical Failures:

As stated earlier, one of the original goals of the de Soto expedition was handed down to de Soto by King Charles of Spain personally. He was desperately seeking a water passage to the Pacific that would better enable trade to the Indies. Just as today, traveling by ship around the Horn of Africa, through the

Arabian Sea, and on to the Bay of Bengal was a treacherous journey during the 1500’s filled with turbulent weather, difficult navigation, and cutthroat pirates. If the Spanish were able to find and claim control over a waterway to the Pacific, they would be able to create a large empire based upon tolling the ancient water highway. Unfortunately for King Charles, this was the first failure of the de Soto expedition. After traveling across the entire Southeastern North American Continent, no waterway was ever found. While this is a failure in one sense, we cannot entirely jump on the de Soto lead Spanish team for not finding this passage. Today because of modern day satellite technology and due to many more years of exploration, we know for sure that no waterway ever existed that would have made travel and trade more efficient for European society. Only during the last century has the Panama canal been built, so in all honesty, de Soto had been order to search for a route that did not exist.

Social Failures:

During their journey across the South, the Spanish army came into contact with many native tribes. The Spanish Crown had already issued orders for the expeditionary party to learn more about and establish deeper relations with the natives for the purposes of trade and control. In studying any early colonial force, especially the Spanish during the 1500’s it would seem to stand to reason that the Spanish held the upper hand in the department of arms and warfare. After all the Spanish armies had muskets, metal armor, and horses. However, de Soto’s army ran into stiff competition from war-proned tribes throughout their trip. Often times the Spanish found themselves outgunned by natives who’s major weapon was the ancient bow and arrow. How could this be? Well, have you ever seen someone try to load a 1500’s musket? Probably not, but if you were to see this attempted, you would notice that at the most rapid of speeds, a good musketeer could only get off about two shots a minute, and that’s a highly optimistic estimate. At those rates, the natives undoubtably had an advantage with their bows and arrows. The Spanish metal armor was no match for an arrow either. Small gaps were almost always present in solid armor and in chain male the odds of an arrow penetrating into the skin were doubled. Luckily for the Spanish, they were smart enough to adapt to a stuffed vest that was much more protective. Some soldiers most likely even began wearing deer hides and hog hides which lessened the impact of arrows significantly. Still, de Soto’s army encountered human losses here and there through their expedition through means of war.

However, the biggest failure that the Spanish made in terms of relations with the natives was the on-slot of disease brought from Europe to the new world. Countless numbers of natives succumbed to plagues and viruses due to a lack of immunities in their tribal societies. We have no way to know exact population loss numbers. The only clue we have is in the written accounts. We know that when Hernando de Soto’s army came through Arkansas they reported large tribes that held exclusive hunting rights to large portions of land and even had political problems with native neighbors. When French explorer Robert de Salle’s men, such as Henri de Tonti, and others arrived in Arkansas in the 1600’s those large tribes were nowhere to be found. In fact, the astonishing thing is that the names of the tribes were not even the same. The written accounts from the de Soto expedition mention tribes and villages with names such as Coligua, Calpista, Cayas, Chaguate, Ayays, and Tula. Later French traders came into contact with tribes with familiar names such as Ugahxpa(Quapaw), Osage, and Caddo. While not proven, there is even some indication that the tribes in Arkansas described by de Soto’s men in 1541 were no longer present in the area during the 1600’s. Could they have just fled the region due to war and disease brought by the Spanish, or could they have died out to the point that no correlation could be made between the 1600’s natives and their ancestors that met the Spanish army? We have proof in the form of tree rings that match the time when de Soto’s army arrived in Southeastern North America. By studying those tree rings, we know for a fact that an extreme drought was taking place. That fact is once again backed up by the narratives left by the de Soto expedition. It is possible that weakened by drought and therefore a lack of food, the natives simply couldn’t face the diseases brought by the Spanish or the warfare perpetrated on them. No matter what, a failure is found in that the Spanish contributed to the loss of many native american lives.

Economic Failures:

Hernando de Soto was also out for riches. He and many of the men with him during the 1539-1542 expedition were veterans of the Mesoamerican and South American Conquests that resulted in mass riches being discovered and taken from natives. This trip into the interior of North America was no different in their minds. Yes, they were looking for a passage to the Pacific, and yes, they were willing to carry out the King’s wishes and establish relations with the natives, but make no mistake, they wanted to find gold! De Soto himself was rumored to have been searching for a cliff along a river bank that was made of one solid emerald. Chalk up another failure. No large amounts of gold were ever found and no emerald cliff was ever discovered.

Personal Failure:

In the end, not only did this expedition cost many of the soldiers their lives, but de Soto himself paid the ultimate price. On May 21, 1542 Hernando de Soto died of some unknown disease. The exact location of his death has been debated over the years. Some scholars believe he most likely died near Natchez, Mississippi, but most have tracked the location to Southeastern Arkansas between the Saline River and the Mississippi. That geographic location still leaves a lot uncovered, but we know by written accounts that de Soto was buried first by his fellow soldiers. When the natives became curious and started to search to find out if de Soto was just gone and would be back or if he had died, the Spanish dug his body up and dumped his body into the Mississippi River. In other words, no physical remains of de Soto have or will ever be found. His body was given as a gift to exploration to the place he discovered. This was perhaps the greatest failure for de Soto personally.

Exploratory Failure:

Many considered de Soto’s expedition a failure since it did not lead other to follow. It would not be until the 1600’s before any explorations or settlement attempts were made in the eastern portion of North America. The English and the French both began to fill in the gaps of the work the Spanish started in the 1500’s. Jamestowne was founded in 1607 by the English on the East Coast of Virginia, and Arkansas Post was established in 1686 by the French along the banks of the converging Arkansas and Mississippi Rivers. Due to an unfavorable opinion of how the Spanish explorations went, the English and the French were much more hesitant to settle or explore in the same manner as the Spanish. Had it not been for the fiasco of the Pánfilo de Narváez expedition in 1527 and the de Soto expedition’s seemingly unsuccessful attempts in 1539, the Spanish, French, and English might have been more inclined to forge ahead with the exploration and colonization of North America.

Successes:

Geographical Success:

Though the initial goal of the de Soto venture, to search for a water passage to the Pacific was a no go, a major success can be found in the fact that the army was able to explore a vast expanse of interior North America and even rule out the possibility of a water route to the Pacific inside the Southeast. To that point, no other European exploratory group had been able to analyze and map the Southeastern portion of the Continent.

This would help later expeditions by the French, English, and Spanish by providing them with some idea as to where exactly the main waterways traversed and the type of terrain that would be encountered.

Exploratory Success:

Early in June 1541, Hernando de Soto personally walked onto an embankment, looked west and became the first European to see the Mississippi River, or so he claimed. There is no guarantee that de Soto was the first to see the River. Although there is some question as to whether or not he was the first to the river, it’s safe to say that the de Soto expedition made a number of significant discoveries that transformed the future of North America and the world. First and foremost must be the Mississippi River. While there is some discussion about the possibility of Cabeza de Vaca, part of the 1527 Narváez expedition, discovering it just years before de Soto, de Soto is no doubt the man that realized the importance of the grand river and made it a standard geographical landmark to European mapmakers.

Other historical significant finds were made such as the discovery of the American Blue Catfish in the Mississippi. One soldier with the expedition noted that what the natives called “bagres” (most likley a catfish) was huge, some by between 100 to 150 lbs and were caught with hooks. Now try to fit that on your plate! Both the army’s of Hernando de Soto in the Southeast and Coronado in the Southwest came into contact with what we know today as buffalo. Cabeza de Vaca of the Narváez expedition was the first European to see buffalo, but de Soto and Coronado both game more detailed accounts of what they called the “giant cows.” Because of natural buffalo trails, such as the famous Southwest trail, which was actually carved by millions of buffalo herding across the landscape, we have always known that the American Buffalo roamed the Great Plains, but without the accounts of de Soto, we would never have had specific acknowledgment of large buffalo populations once extending all the way into Missouri, Louisiana, and Arkansas to the Mississippi River.

Ecological Success:

Not only did the army find and record new species that were unknown to Europe, but they also introduced a few new animals to the new world. The famous Arkansas Razorback is a product of the de Soto expedition. They were, as stated earlier, carrying about 220 hogs with them. Inevitably many of those domesticated hogs strayed from the pack and thrived in the Arkansas climate with no real predetorial threat. Those hogs became large, wild, fierce, and what we call today the Arkansas Razorback. The Spanish also introduced wild turkey’s and horses to the region. Natives that came into contact with the army also got their first ever look at Africans.

Political Success:

De Soto’s army was also the first to give accurate and detailed descriptions of the Native Americans in the Southeast. They came to understand the diverse and sometimes hostile political culture that existed between native tribes. They cultivated those political divisions off of one another.

Some trade was established through the de Soto expedition. Evidence of this exists in the archaeological form of Spanish beads found at native sites such as McRae, Georgia and Parkin, Arkansas, both dating to the 1540's.

Cognizant Success:

The de Soto-lead Spanish exploration of 1539 to 1542 would eventually lay the building blocks for later French and English settlement. The French especially learned from Spanish mistakes. They understood that true trade and control could not be established without the French taking the lead and integrating themselves into native society. The French also learned from the Spanish that large armies would do nothing but spread terror and fear through Native North America. Instead, the French opted for a more unique approach. They sent small numbers of fur traders, called “coureur de bois,” not professional soldiers, to make contact with Native Americans. This approach worked in multiple location including the Southeast, the Midwest, and the Northeast. Eventually the French would have the upper-hand until the English began to expand and encroach further west with time.

Most likely to be considered the biggest success of the de Soto expedition is the knowledge gained by the Spanish about how to survive in this new environment. De Soto’s army learned very fast that living and fighting like traditional European armies was not going to cut. If they wanted to survive they first had to learn to live like natives. It is likely that as their journey grew longer, they evolved from even dressing like Spanish soldiers to wearing hides just like natives. They learned that musket warfare could be the death of them. Instead they relied on the smarts and tactfulness of their leader Hernando de Soto to scheme and plot against the native to gain the upper hand in times of trouble. De Soto learned to use propaganda, word of mouth, and the tightly connected native trade and diplomacy routes to spread world of how dangerous he was. The more natives knew of his army’s power, the safer the army would be. It is very likely that tribes from Florida to Canada knew of de Soto and heard of his warfare might.

Ultimately:

The bottom line is that de Soto while not completing his army’s exact tasks, still passed on important skills learned and more importantly geographical and political knowledge. More archaeological work is needed to fully understand the route and discover the remaining mysteries of the expedition of Hernando de Soto. One thing is for sure, to label this as just a failure would be to slight de Soto and his men exponentially. Many of their finds and discovered knowledge merit the term “Successful Failure.”

No comments:

Post a Comment